Wolves, anyone?

Chapter One

Her headlights sliced through the night, a yellow blur of road lines flashing past. The desert air, warm as breath, wound her hair into spirals, circled her neck.

Malia hit the brakes. Dust rose in her high beams, lingering shapeless like fog. Her only company was the hum of the Jeep. Her breaths came fast, the seatbelt cutting across her chest. She killed the engine, killed the lights. Darkness knocked into her, and her eyes pushed against black hunting for even a speck of light.

She waved a hand in her face. Nothing. “Hello!” Her voice fell away fast. “I’m here!”

When she’d arrived earlier that day to check in with her supervisor, she marveled at the sunlit desert, its plain of dry grasslands surrounded by erupting mountains, so striking compared to the rolling hills of the Midwest. She’d never felt so weightless, moving under Arizona’s massive sky with no more significance than a snowflake on fire. But at night, Malia felt connected, rooted to the landscape the way the immovable hoodoos sprouted from hilltops.

As each minute passed, the sky covered Malia in more glitter. “Hello stars!” Faint currents swirled over her like butterfly kisses.

She unlatched herself and stood on the seat but she wanted to be higher, closer to the night sky that wrapped her in purpose. She stair-stepped her way from dash to doorframe to headrest until she balanced like a warrior, one foot on the windshield, one on the roll bar. A rumbling tickled her throat and she let her laugh spill out. Why bother stifling it? No one was listening. No one was watching. This moment belonged to Malia.

Her muscles started to uncoil after two days of driving. She tore off her shirt, jumped from the Jeep and was off racing down the desert road, each stride pumping out the kinks. To keep her path straight so she wouldn’t stray and stumble into the gravel shoulder, she focused on those black giants in the distance that gradually took form, the mountains that rose against a tapestry of stars that reshaped the heavens as new bodies of light appeared. After what must have been a couple football field lengths, Malia raised her arms as if crossing a finish line. She lay down and fanned out her long hair, black on black. She’d hear a car a mile away, or see a beam of headlight breach the dark, should any come down this one reminder of man’s intrusion. The sun-soaked asphalt warmed her back. The smell of creosote hinted at recent rain. A tiny but mighty scratching drifted from the east—a rodent searching under rocks for dinner. Hoofed feet too, mule deer probably, or javelina, clacking on outcrops. Then the squall of captured prey, snatched by an owl with silent wings and lethal speed.

Malia watched the stars swell. She reached up, brushed their glow with her fingertips. “Mom, look, I’m here. Can you see?”

As if her words were a cue, Malia heard it. A distant howl working its way through the night rising and falling like a ribbon rides a gentle wind. She held her breath to listen, convinced she had conjured it, but then another bay, deeper and with a sudden change in pitch, answered. A chorus performed now, multiple voices, throats swelling, beckoning a reunion of the pack.

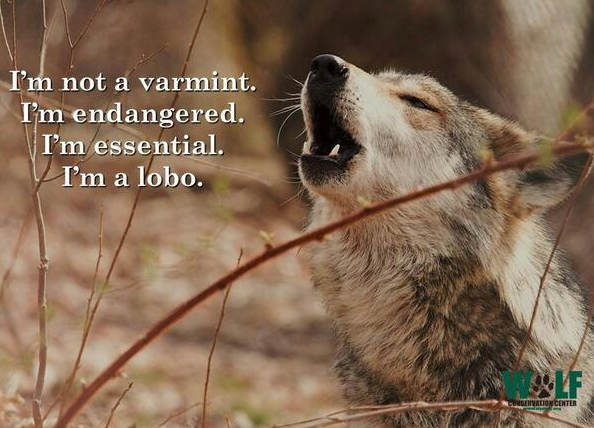

She imagined the night air a whisper tickling her ear with the news her mother had waited her lifetime to hear. The Mexican gray wolf was alive and well again in its historic range, serenading the mountains that had been lonesome so long, but what was the lobo doing this far south? The primary zone in the Blue Range Wolf Recovery Area in Alpine was two hundred miles north.

Mom would know.

Their plaintive wails nudged Malia’s sorrow from that secret spot in her bones where no one could see. After all the years watching her mother work to see lobos reintroduced to their desert home, this was the trip Malia had wanted to take with her, driving a thousand miles to walk the earth where wolves were allowed to leave their footprints again, after decades of near extinction. But Dad always nixed the trip. Maybe next year, Honey, Mom would say. Mom never got a next year. Malia shoved away the image of her father back in Kansas City, sitting alone between the walls of the house that no longer rattled with Mom’s energy. Malia closed her eyes and lay there like an undiscovered corpse no one knew to miss. Only the stars could see the dolor dig its claws into her, and Malia trusted the stars to let her be.

Then came another crest of howls. She pictured the wolves’ golden moon eyes, so human-like, captivating people throughout history with their intensity, making them wonder if wolves could see their souls. She remembered holding her breath when vets at the Endangered Wolf Center returned an alpha to his pack after a long illness. All the playfulness and tail wagging he received upon his return made her wonder why there was still so much wolf hating in the world. She remembered her first glimpse of them via den cameras, pups born to a nurturing, watchful mother that would one day be released into the wild to roam the desert where she now lay.

Malia opened her eyes to a hairline sliver of moonlight etching a smile in the sky. She stood to go, finally able to make out the white on her running shoes. She listened as each new howl swelled, trying to count. Four wolves could sound like a dozen as their voices modulated and scattered past ridges and trees. Malia broke into a sprint again, wondering how it’d feel to travel in the security of a pack, owning the night.

She barely saw the black hulk of Jeep as the baying died down. The sudden quiet left room for her mother’s voice. People could learn a lot from wolves, Malia, if they paid attention. The way they hunt together to provide for everyone. The way they mate for life. The way the alpha watches for danger while the whole pack raises the young, pitching in like family should.

A shooting star bloomed across the sky. “One one thousand. Two one thousand. Three…” Its glow flickered and faded on the horizon. Malia’s body felt heavy now. She needed some sleep at least, before her supervisor came knocking to explain exactly what a volunteer interpreter does for the National Park Service all summer long.

She stood outside the Jeep’s door, her own panting filling her ears. She fumbled in the seat for her shirt when her blood turned brittle.

She wasn’t alone.

A velvety touch brushed her bare shoulder. “Don’t move.” A deep voice. The heat of breath on her back.

“Who’s there?” Malia turned around. A horse nickered so close, she expected whiskers on her face.

“So move if you want to,” the guy said. “But there’s a rattler under your tire. You like diamondbacks?”

Malia imagined the viper coiling around her ankle. “Shit. What do I do?”

She heard the rider dismount and slowly back his horse away. “Forget your shirt and walk toward me,” he said. “Nice and slow.”

“I can’t see you.”

“So stop looking and follow my voice.”

She slid a foot forward, her shoe grating over gravel. “Is that you, Kyle?” She’d met him briefly in the visitor center earlier, happy to see someone about college aged, like her.

“You wanna talk, Malia? Or do what I say?”

Malia kept her mouth shut.

“Good. Now baby steps. No more sprinting.”

Malia tightroped her way toward the man who’d been watching her, seeing her run when she thought she was invisible.

“Nice and steady, now.” Kyle’s voice was confident, yet still disconnected somehow. “Why you out here in the dark, anyway?”

Malia made out the ghostly hulk of his white horse. “I like the dark. It’s quiet. But rattlers? Definitely new territory.”

“You’re almost here.”

Malia reached for his hand but couldn’t find it so she stood there in her black sports bra, at least feeling invisible. Still reaching, she connected with Kyle’s cheek. It was wet. Warm. Malia was sweaty herself, her blood still pounding after her sprint, and the discovery that she wasn’t alone.

Kyle grabbed her wrist, harder than he needed to, and pulled her hand off his face. His palm was wet too. He must have ridden hard to work up such a sweat on a cool night when the horse was doing most of the work. He stepped toward the Jeep. “It’s moving on now.”

Malia tried to look. “How can you tell? You can’t see a thing out here.”

“I can see plenty.”

Malia crossed her arms over her chest, looked again.

“It’s called a sixth sense,” he said. “Wait till there’s a full moon. Even scorpions see their shadows then.”

“What do you mean, sixth sense?” Malia flexed her wrist where Kyle had latched on.

“Desert sense. You either get it—or get hurt. That snake craved your heat—from the Jeep. So next time you go streaking out here, better think twice about where you step.”

“Good tip, Cowboy. Thank you. Am I safe to get my shirt?”

“You can get your shirt. As for being safe, that’s not for me to say.”

Kyle’s horse nudged her again. She ran her hand down its nose, soothed by the warmth. Leather creaked as Kyle settled back in the saddle. He clucked his tongue and Malia stood listening as they clacked away on the pavement, then off road. Hooves pounded over packed earth and faded. She licked her lips, tasting the dust Kyle’s horse kicked up.

She revved the Jeep, made a U-turn, and drove down 181 toward Bonita Canyon Road, steering with her knee as she reached up to catch the air, let it scour her clean. Her headlights hit the gateway sign for Chiricahua National Monument too late. She threw it in reverse and turned toward her National Park Service trailer, home-simple-home for the rest of the summer. Trailer B was the dingier of the two, rust streaking the siding and the front porch step crooked and steep, but it felt good to park. She slung her duffel bag over her shoulder, grabbed the box from the back seat, setting the groceries she’d gotten in town on top, and stepped carefully onto the porch.

Once inside, fatigue hit, but she stayed standing, looking at the fluorescent light pouring through the narrow doorway of the mini kitchen. Her kitchen. It was bare bones living, but Malia felt more at ease in Arizona after nine hours than she’d felt the last three years back home with no one but Dad as a roommate.

The trailer was hot and stuffy, the cheap carpet giving off a hint of smoldering plastic. Malia slid the taped-up box of her mother’s keepsakes out of the way, stirring up dust on the square of linoleum flooring that was her entryway. She wiggled open a creaky window and pressed her face against the screen as the night air pushed in.

In the bathroom, she flicked on the light and reached for her toothbrush, only to drop it when she saw her wrist. A handprint wrapped around it, dark red—where Kyle had grabbed her. Something colored her fingers too, her palm, but only on the right hand, the one that touched his face. It had felt like sweat, but now? Was it paint? Or oil? She swiped her clean fingers over the handprint, smearing parts that were still wet but gummy now.

Malia startled as a far-off cry drifted in the window. It was high-pitched, mournful—nothing like any howl she’d heard while tagging along with Mom studying wolves. The wail came again, closer this time. It brushed her neck, crept up like fingers raking her hair. What kind of animal made a shriek like that?

With the faucet on warm, she rubbed her hands under the noisy stream. The sink basin turned red.

Blood red.

Chapter Two

In the morning, Malia’s boots crunched over parched soil as she followed Ernie to the old ranch house on the national park site. With a simple front door no different from the side entries, and no shutters or discernible landscaping, Hideaway Ranch looked sturdy, practical, and pleasant, its two stories a perfect box shape with a forest-green roof protecting the coral-colored house. The canyon walls in Chiricahua pushed up around Malia, cradling her and the historic homestead among cypress and oaks that climbed the ridge.

“Let’s get to it,” Ernie said, unlatching a ring of keys from his belt loop. His park service shirt matched his tawny handlebar mustache which shifted cock-eyed when he winked. “You and I are the Hideaway tour guides for this summer.”

“Only two of us?”

“Dean, our chief of safety, will do backup in a pinch, but we’re a small operation so volunteers need to know as much as us park rangers. You’re on duty in a week.”

Ernie jiggled the doorknob, worked in the key. “When you come open up, you’ll have to use your muscle. This blasted thing jams now and again, no matter how much we fiddle with it. Funny thing is, it closes smooth as butter. It’s no secret Evelyn’s spirit doesn’t care for visitors.”

Malia ran her finger along the metal edge of the donation box mounted on a split-rail post. “That’s supposed to be a joke, right?”

Ernie smiled, his laugh lines crinkling.

A cool morning breeze rustled a line of oaks at Malia’s back. She used her hands as a visor, looked up the adobe walls. The second story windows reminded her of dark eyes on a lifeless face. She pictured the old woman standing there behind a lace curtain, staring and scowling before yanking down the shade. “How long’s she been dead?”

Ernie leaned a shoulder into the door, convinced it to open. “Sixty years now. Evelyn was a tough old homesteader, managing this place till her final breath.” He stepped off the threshold, held out his arm. “After you, my dear.”

Malia stood in the entryway as her eyes adjusted. Hideaway Ranch smelled old, but a lived-in kind of old, as if Evelyn would come shuffling around the corner with a headless chicken ready for plucking. “So she lived here all alone, even after she went blind?”

A gust of wind blew the door shut behind her, and the house seemed to exhale a breath held too long.

“Yep, she stayed till her very last day. Her stubbornness was more famous than Geronimo. But loneliness got her in the end. Legend has it she died of a broken heart.”

Malia laid her palm on the agave-themed wallpaper, yellowed and brittle and edged with dark, wide trim. “That sounds like a juicy story. I need details.”

“Ah, you’ve got a rich imagination. That’ll serve you well as interpreter here, long as you stay true to what we know is fact. But no, Evelyn’s husband died when she was fifty, and her final companion was canine—half-wolf, according to her diaries. Obviously didn’t set well with ranchers ‘round here, so she kept the pooch hidden, like she did herself in later years.”

Malia lost track of what Ernie said after that. Half-wolf? Memories of KoKo, her own wolf-shepherd mix, sucked her breath away. Koko had come from a litter her mom had rescued when Malia was five. Growing up together, Mom always said they were like sisters, each leading the other to mischief one minute, then snuggling the next. Malia could still feel KoKo’s soft muzzle and bushy fur, the weight of her paw, her warm panting, if Malia stopped petting too soon.

Ernie opened a breaker box and turned on a bank of lights. “These control the whole house, except the stone house—that one’s a stickler. Always has been.”

“What’s the stone house?”

“For starters, where Evelyn’s body was found.”

“We give tours through there?”

Ernie laughed. “Indeed we do. But there’s no chalk outline of her body. We simply tell visitors she died peacefully at home. But initially, the stone house served as shelter during the Apache Wars. Natives weren’t keen to homesteaders moving in. Made it clear they weren’t giving up their land without a hell of a fight. You know much about Cochise?”

“Heard of him. Apache chief, right?”

“Right. When you head up the mountain, look for his profile as if he’s lying on his back watching the sky—Cochise Head. It’s in the rock formations.”

“What do you mean? Carved into the mountain like Crazy Horse?”

“Somewhat, but Cochise Head isn’t man-made. Showed up all on its own. His body was buried in secret somewhere in Cochise Stronghold. That’s where he and a couple hundred followers hid out for years. To this day, no one knows the whereabouts of his bones but people still search. Seems folks are always hunting for something that’s lost. I tell visitors that his face in the rock is how he reminds us this is his land and he never had any intention of leaving it after the white men drove out his people.”

“Pretty convincing point.”

“I don’t argue with him. Anyway, once the Apaches were all gone, the stone house became a cooler for awhile. Now it’s just used as storage. It’s all in here.” Ernie handed Malia a packet of literature, curled at the edges like it’d been recycled from earlier volunteers. “We’ll start in the dining room and work our way upstairs. Take notes and ask plenty of questions. Visitors want to know all sorts of things. And some of it is bound to catch you off guard.”

Malia followed Ernie to a built-in bookcase behind the table. A skinny closet to the side held cleaning supplies. Ernie pulled out a feather duster and ran it over knick-knacks and worn journals. “A couple times a week, you’ll want to tidy the place. Desert dust has a mind of its own, resting on these diaries like it has as many stories to tell as Evelyn. But keep your fingers off the artifacts. Skin oils and historic treasures don’t go together.”

“So no sneaking into Evelyn’s secrets, huh?”

Ernie turned from his dusting to look straight at Malia, the whimsy in his eyes gone. “No, afraid not. I’ll tell you everything you need to know for the tours, okay Malia? But emergency gloves are on the second shelfcloset, in case you have to touch something.”

Malia nodded wondering why she would have to touch something, but Ernie was moving on.

They walked through the sitting room, family photographs framed and fading on the walls, a crocheted blanket draped over a couch with saggy, floral cushions. Malia pictured Evelyn snuggled there on a chilly night, her wolf-dog warming her feet like she and Mom used to do with Koko. The memory hurt, but there was no harm in fantasizing about sitting next to Evelyn, chatting softly as music crackled from an old-time radio…the stubborn, old woman couldn’t die on her.

When they started upstairs, the wood moaned under their weight. Ernie rounded the hallway to the bedrooms. Malia stopped to look out the landing window. The mountain view was so majestic it stilled Malia’s breath. Hoodoos, with stony faces that change expression in shifting light, made you feel watched over, a canyon full of companions. Maybe that’s why Evelyn stayed here, even if she couldn’t see in the end, because the land felt like the family she’d lost and she had a loyal dog to chase away the loneliness.

Movement in the distant scrub caught Malia’s eye, an animal loping along toward Hideaway as if it were headed home, but when she blinked, what looked like a wolf reappeared as a mule deer. She took the vision as a sign that Chiricahua was exactly where she was supposed to be.

Malia creaked up the final half flight of stairs and stood in the hallway guessing which room Ernie might be in. She heard a footstep behind her, swung around to look—maybe there was a back staircase where Ernie had circled around. But he wasn’t there.

“In here, Malia,” he called from the bedroom on the left.

“Yeah, okay.” But Malia kept her feet in place, rocking back and forth, testing the floor. No creaking from where she stood. “Crazy old house.”

After Ernie explained the significance of every quilt and mirror and hairbrush on the second floor, they exited a door on the east side and down a staircase. “Evelyn had these stairs built after turning the place into a dude ranch. Guests could come and go as they pleased.”

On the back porch, a drying rack for milk bottles still stood, seemingly ready for Evelyn’s fumbling hands to fill it. Malia could almost smell fresh-cut firewood stacked in the wood box under the kitchen window. The very soil seemed to hold the footprints of the old lady and her wolf-dog milling around the property.

Past the well where the canyon walls rose, evergreens reached skyward like clipped birds trying to fly. Malia’s legs itched for a long walk through the quiet trails, the Wonderland of Rocks, as Chiricahua had come to be known. She could rest on a rock, imagine the breeze in her hair was her mother’s fingertips, the rustle of wind her soft voice.

“Time to lock up,” Ernie said. “I’ll show you how to set the alarm.”

“There’s an alarm on this place?” Malia turned back to look at Evelyn’s simple, boxy house again, standing stark in the lonely canyon.

“Got installed just before you came. We’ve found doors unlocked, things moved around.”

“You’re not trying to spook me, are you, Ernie?”

“You spook easily, do you? A strong girl like you, so independent and far from home?”

“No way.” Malia bopped the brim of Ernie’s park ranger hat. “It’s probably local kids goofing off, don’t you think?”

Ernie held her gaze, sized her up. Can he see through me, Malia wondered. Does he know I’m here because ‘far from home’ is the only place I can stomach?

“Maybe,” he said.

“It’ll take more than a few thrill seekers to scare me away. Promise.”

Ernie’s smile pushed his long sideburns into his ranger hat. “On that note…” Ernie nodded to someone standing behind her. “I’ll hand you over to your next tour guide, soon as we lock up.”

“Oh,” Malia said as she turned, surprised to see someone standing there.

“Nice to see you again.” Kyle’s old-fashioned formality fit right in with the historic setting. He wore the long-sleeved yellow shirt and forest green pants of the fire crew.

“Well, I wouldn’t exactly call it seeing last—”

“No,” Kyle interrupted. “We barely crossed paths at the visitor center yesterday. Malia Rudy, right?”

“Yes.” She played along, shaking Kyle’s hand while looking for cuts on his cheek that would explain the blood, but with the sun at his back, his face was hidden in shadow.

“Kyle here knows everything there is to know about Chiricahua.” Ernie gave the doorknob one last rattle. “He’s a descendent of Evelyn’s. The Sunneborn Ranch is down around the corner.”

“No kidding,” Malia said. “I didn’t realize she ever had kids.”

“That’s another piece of her sad history.” Ernie turned to go.

“Sad how?”

“After she lost her husband, her second son, Kasper, died when he was about your age, in the copper mines. But that’s a story for another time.” Ernie clapped Kyle’s shoulder. “You two should get going up the mountain before afternoon storms roll in.”

“I’ll grab our packs and meet you at the visitor center,” Kyle said to Malia.

She watched him walk away, his shirt tight across broad shoulders. His step was graceful, confident, but his brush-off about meeting up last night put her on guard.

“Oh. I nearly forgot.” Ernie tucked a piece of paper in Malia’s hand. “Here’s the alarm code. Now that’s for your eyes only. Memorize it today, then lose it. Understand?”

Malia nodded. “You all sure put a lot of trust in a girl not even done with college.”

“You’ve been thoroughly checked, trust me. Remember all those forms your folks signed when you applied? The background checks?”

Folks. Right. Malia had forged Dad’s name on everything related to getting to the desert. She could’ve gotten his signature by shoving forms under his nose and mumbling about her final semester as he stared down sales figures. But it made her feel better to sign the papers herself. He would never have agreed to her coming here, chasing a dream that belonged to her mother, he’d said. So Malia took charge of making the dream her own. She’d turn 21 this summer. It was her time.

“Park Service depends on volunteers,” Ernie continued. “This land needs protection. Too much history running through these old mountains. Too many untold stories.”

“I bet.” Malia tucked the alarm code in her pocket and looked up to where the ridge met that all-seeing sky, wondering what kind of stories it witnessed that no one lived to tell.

This is such an awesome post! I love your blog!

LikeLike